I found Ashesi five years ago when a colleague told me about the university’s objective – “Educating a new generation of ethical, entrepreneurial leaders.” Therefore, as I attempted similar objectives at my home university, I applied to the Fulbright Fellowship program though the Institute of International Education (IIE) and the U.S. State Department’s Department of Education and Cultural Affairs to come here to Ashesi University College in Ghana. Awuah (the university’s founder) and the Ashesi team appeared to be attempting the same vision I had, that integrity business is possible, that educating today’s students for leadership tomorrow can make a difference in the world, and that – as Margaret Mead put it years ago – one should “never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed people can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.”

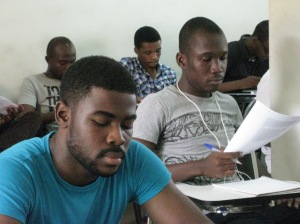

November coaching session with senior thesis students

This story harks back to my sister’s question last year, “so, what are you actually going to be doing there?” And multiple people’s questions summarized as, “why Africa?” I came here to teach and learn about improving our global world through “good business.”

This year at Ashesi, I jointly located myself in the business department and in the liberal arts department. In business, I taught organizational behaviour, the field in which I did my PhD work. In liberal arts, I taught three of the required leadership curriculum courses. Leadership is a central part of the liberal arts core here. The subject matter here spans from internal values analysis and self-assessment, to reading and discussing theory about leaders “out there,” learning political and philosophical tenets of “good society,” and applying lessons through service learning and studies of servant-leadership. The leadership objective is to equip students with the capacity to lead positive change in this developing world. In their majors, students learn skills and technical knowledge specific to their careers.

Vodafone Great Debate about Social Responsibility, Ashesi Strategic Marketing student teams and Dr. Neville as 1 of 3 judges

Going into the leadership series, I knew the least and therefore learned the most about African philosophy and political theory central to Leadership II: “Rights, Ethics and Rule of Law.” Through the semester, students and I analyzed social and political theory towards building and nurturing a “good society” where citizens have rights and yet are also expected to uphold responsibilities. Together, we crossed vast territory.

In all of my leadership courses, I stressed my own understanding of leadership as the leading we each do every day through every choice and action – I call this “leadership with a little l.” The same principles apply to little l leaders as apply to “out there” leaders, people who are hierarchically in charge or voted into office or appointed with explicit fiduciary responsibility to a particular stakeholder group. I call this “out there” leadership, “leading with a Big L.”

Big L leadership is what most traditionally gets taught or studied in formal education. Little l significance depends on a personal empowerment view, an inter-connectedness, a belief that each individual and each action is somehow connected to every other individual and action.

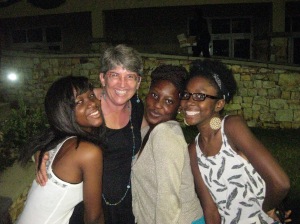

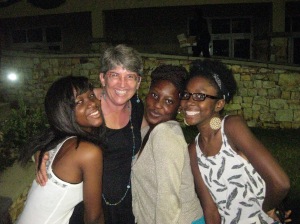

International Night, 2013

I suspect my American students think I am being a bit of a goodie-two-shoes when I say that they are the source of change for tomorrow’s world, no matter what career they pursue. Here, the Ashesi students take on the responsibility of making themselves that source for change – they are already the elite merely by attending college whether on full scholarship and first generation college or full-pay having already schooled abroad. These students must absolutely be, or quickly become, both little l leaders and big L leaders in order to gather a critical mass of committed change makers.

When I return to the U.S., I will argue that the American students have an even greater responsibility to become little and big L leaders than I had ever imagined, simply because they/we have been born into so much privilege.

And so to my sister who wanted to know what I would do here – I see now more clearly what I have done. I have coached and taught over 200 young people, helping to empower them to create their own forms of “good society” as they go out into the world of commerce. I have offered them comparative models and comparative principles from my culture as I absorbed principles, paradigms, and cultural practices from their cultures. I have also joined a community of scholars by supervising senior thesis projects, collaborating on joint research agendas, and probing into possibilities for education innovation.

Faculty meeting research presentation – Neville on Liberal Arts findings

As a researcher, I am learning from Ashesi alumni, people already out in the world practicing “good business.” Alums, through their stories, provided data from which I can build hypotheses about the capacities these young professionals have most relied upon in order to be the high integrity change that they hope to see in the world. My research outcomes will be recommendations about curricular approaches – especially for business teachers – for teaching integrity and courage (two emergent themes). The links between integrity and innovation, business and technology, theory and application, are precisely why I entered academia as a teacher-scholar 10 years ago; it is precisely too why I so firmly believe that liberal arts and business, computer science, engineering, nursing belong together. (But perhaps that is itself a different conversation.)

For now, I’ll stop with a shared hope to change the world, albeit through the small and ever growing band of committed individuals. Perhaps this is precisely the character of grass-roots diplomacy and change which Senator Fulbright imagined when introducing the Fulbright Scholars programs 60 years ago.

Note: I am deeply grateful to all who have made this learning journey possible, both here in Ghana and in the U.S., not the least of whom are my departmental colleagues at Southwestern, my home university, for “holding down the fort” while I’m away.

Rainy season brings the obvious — rain. What I have never considered are implications of rain beyond flooding and washed out roads. In fact, rainy season here in the Eastern Region, Ghana, the most beautiful birds, insects, flowers, fruits have flourished with the rain. Okay, sometimes, I’ve been caught in the rain and one time an uninvited critter came in from the rain, but beyond that, the now cool season has much to brag about. (My apologies to anyone who’s running on low bandwidth and therefore can’t easily see the picture show).

Rainy season brings the obvious — rain. What I have never considered are implications of rain beyond flooding and washed out roads. In fact, rainy season here in the Eastern Region, Ghana, the most beautiful birds, insects, flowers, fruits have flourished with the rain. Okay, sometimes, I’ve been caught in the rain and one time an uninvited critter came in from the rain, but beyond that, the now cool season has much to brag about. (My apologies to anyone who’s running on low bandwidth and therefore can’t easily see the picture show).